Miss. high court declines to block inmate hearing

Published 12:26 am Tuesday, July 28, 2009

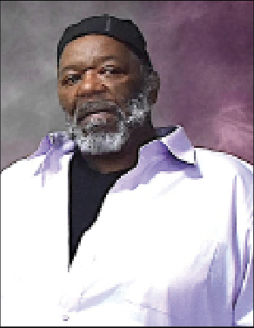

The Mississippi Supreme Court will allow inmate Van Gray a hearing on whether he has lost a chance to earn time off his sentence because of how the Legislature wrote a 2004 law.

The law eliminated earned time and trusty status for drug offenders. Gray said that eliminated his chance to earn time off his sentence by working or by just being a good inmate.

The Supreme Court this past week declined a request from prosecutors to overturn a state Court of Appeals ruling that sent Gray’s case back to Lamar County.

Gray was charged in October 2001 with selling less than 0.1 gram of cocaine to an undercover officer in Lamar County. He pleaded guilty in October 2004 and was sentenced to 15 years, with eight years suspended.

Between Gray’s arrest and sentencing, the Legislature enacted a law that eliminated earned time and trusty status for drug offenders.

In his post-conviction petition, Gray argued that the way corrections officials applied the law his chance to earn time off his sentence was eliminated.

In a post-conviction petition, an inmate argues he has found new evidence — or a possible constitutional issue — that could persuade a court to order a new trial.

Lawmakers envision the 2004 law as a means of allowing nonviolent prisoners to earn a day off a sentence for every day worked in a trusty program. Previously, inmates had been allowed one day off for every three days worked.

Supporters said the change would get more nonviolent offenders out of prisons, freeing beds for other state inmates backed up in local jails.

Gray argued in court documents that the law, as written, prevented him from achieving trusty status, denied him the ability to earn additional time off and, thus, was an increase in punishment.

Circuit Judge R.I. Prichard III rejected Gray’s arguments in 2006, saying that the authority to grant earned time is not a form of sentencing or punishment but was to encourage good behavior among inmates and to help ease overcrowding. Prichard said the law was permissive, therefore, earned time was not an entitlement. Prichard also said Gray’s sentence was within the statutory limits for the crime and that the legislation which took away the earned time did not increase the amount of punishment for Gray’s crime.

Judge Donna M. Barnes, in the Appeals Court’s October ruling, said Gray raised a valid point about how the law was being applied to inmates whose drug arrests occurred before the statute took effect in April 2004.

Barnes said Gray deserved a hearing to determine whether he was hurt by the 2004 law.

Barnes said the trial judge should obtain information about how the trusty program works, how many prisoners like Gray are granted trusty status and what the requirements are for trusty-earned time.

Without that information, Barnes said a court cannot determine whether Gray was subjected to an improper retroactive law.

Prosecutors argued Gray was not a trusty when the new law took effect, so the application of the new law to him did not constitute an ex post facto violation.

Prosecutors said trusty status and trusty-earned time are a special designation that have to be earned.

They said the best Gray would be entitled to was an administrative classification review by corrections officials to determine whether or not he could have been granted trusty status at some point during his imprisonment under the rules in place at the time he committed his crime.